- Home

- Dan Simmons

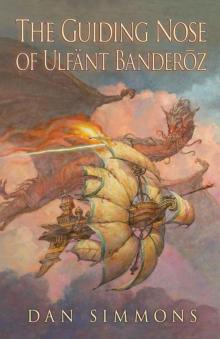

The Guiding Nose of Ulfant Banderoz

The Guiding Nose of Ulfant Banderoz Read online

The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Banderōz

Dan Simmons

Subterranean Press 2013

The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Banderōz

Copyright © 2009 by Dan Simmons.

All rights reserved.

Dust jacket and interior illustrations

Copyright © 2009, 2012 by Tom Kidd.

All rights reserved.

Print version interior design Copyright © 2013

by Desert Isle Design, LLC. All rights reserved.

Ebook Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-557-4

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

www.subterraneanpress.com

The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Banderōz

In the waning millennia of the 21st Aeon, during one of the countless unnamed and chaotic latter eras of the Dying Earth, all the usual signs of imminent doom suddenly went from bad to worse.

The great red sun, always slow to rise, became more sluggish than ever. Like an old man loathe to get out of bed, the bloated sun on some mornings shook, quivered, staggered, and rippled forth earthquakes of protesting rumbles that radiated west from the eastern horizons across the ancient continents, shaking even the low mountain ranges worn down by time and gravity until they resembled old molars. Black spots poxed and repoxed the slowly rising sun’s dim face until entire days were all but lost to a dull, maroon twilight.

During the usually self-indulgent and festival-filled month of Spoorn, there were five days of near total darkness, and crops failed from Ascolais through Almery to the far fen borders of the Ide of Kauchique. River Scaum in Ascolais turned to ice on the morn of MidSummer’s Eve, freezing the holy aspirations of thousands who had immersed themselves for the Scaumish Rites of Multiple Erotic Connections. What few ancient upright stones and wall-slabs that were still standing at the Land of the Falling Wall rattled like bones in a cup and fell, killing countless lazy peasants who had foolishly built their hovels in its lee over the millennia just to save the cost of a fourth wall. In the holy city of Erze Damath, thousands of pelgranes—arriving in flocks the size of which had never been seen before in the memory of man and non-men—circled for three days and then swooped down, carrying off more than six hundred of the most pious pilgrims and befouling the Black Obelisk with their bone-filled droppings.

In the west, the setting sun appeared to pulse larger and closer until the forests of the Great Erm burned. Tidal waves washed away all cities and vestiges of life from the Cape of Sad Remembrance, and the ancient market town of Xeexees, only forty leagues south of the city of Azenomei, disappeared completely one night at three minutes after midnight during the height of its crowded Summer Fair; some say the town was swallowed whole in a great earthly convulsion, some say it shifted in an eyeblink to one of the unbreathable-air worlds of the dodge-star Achernar, but whichever was the case, the many residents of the metropolis of nearby Azenomei huddled in their homes in fear. And during all these individual tragedies, more than half the surrounding region once known in better days as the Grand Motholam suffered floods, droughts, pestilence, devaluation of the terce, and frequent darknesses.

The people, both human and otherwise, reacted as people always have during such hard times in the immemorial history of the Dying Earth and the Earth of the Yellow Sun before it; they sought out scapegoats to hound and pound and kill. In this case, the heaviest opprobrium fell upon magicians, sorcerers, wizards, warlocks, the few witches still suffered to live by the smug male majority, and other practitioners of the thaumaturgical trade. Mobs attacked the magicians’ manses and conclaves; the servants of sorcerers were torn limb from limb when they went into town to buy vegetables or wine; to utter a spell in public brought instant pursuit by peasants armed with torches, pitchforks, and charmless swords and pikes left over from old wars and earlier pogroms.

Such a downturn in popularity was nothing new for the weary world’s makers of magic, all of whom had managed to exist for many normal human lifetimes and longer, so at first they reacted much as they had in earlier times of persecution: they shielded their manses with spells and walls and moats, replaced their murdered servants with less-fragile demons and entities from the Overworld and Underworld, brought up jarred foods from their vast basement stores and catacombs (while having their servants plant vegetable gardens within their spell-walled grounds), and generally laid low, some laying so low as to become literally invisible.

But this time the prejudice did not quickly fade. The sun continued to flicker, vibrate, cause convulsions below, and generally offer almost as many dark days as light. The scores of human species on the Dying Earth made common cause with the thousands of no-longer-human sort—the ubiquitous pelgranes and Deodands and prowling erbs and lizard folk and ghosts and stone-ghouls and Saponids and necrophages and visps and burrowing dolorants who were merely the tip of this truly terrible non-human icespike—and that common cause was to kill magicians.

When the unpleasant realities of this particular wizard-pogrom began to sink in, the various magicians of Almery and Ascolais (and other lands west of the Falling Wall) who had once belonged to the now-defunct “Fellowship of the Blue Principles” or its successor-organization, the so-called “Renewed Green and Purple College of Grand Motholam,” reacted in ways consistent with their character: some fled the Dying Earth by unbinding the twelve dimensional knots and slipping sideways to Archeron or Janck or one of the other co-existing worlds discovered by the old Aumoklopelastianic Cabal; a few fled backward in time to more felicitous Aeons; more than a few took their motile manses or self-contained glebe-globes and made a run for it through the galaxy and beyond. (Teutch, a recognized Elder of the Hub, brought along his entire private infinity.)

A very few of the magicians who were more self-confident or curious or hoping to prosper through others’ misfortune or simply bold (or perhaps merely much more prone to melancholy) took the risk of remaining on the Dying Earth to see what transpired.

· · ·

Shrue the diabolist was more sanguine than most. Perhaps this was due to his age—he was older than any of his fellow thaumaturges could have surmised. Or perhaps it was due to his magical specialty—most professional binders of demons and devils from the Overworld, Underworld, foreign stars, and other Aeons died young and in great pain. Or perhaps it was due to a rumored broken relationship and broken heart many millennia in his past. (Some whispered that Shrue had once loved and bedded and wedded and lost Iallai, she who had been the entity Pandelume’s favorite dancer and the originator of the Dance of the Fourteen Silken Movements. Others whispered—even more softly—that Shrue had tumbled in thrall to one of his male apprentices back when the Mountains of Magntaz were still sharp, and had retired from magical life for centuries when the beautiful young man had stolen Shrue’s most powerful runes and run away with a leather-bound Saponid from the night-town of Saponce.)

Shrue had heard all of these rumors and smiled—albeit sadly—at them all.

When the Great Panic came this time, Shrue the diabolist closed up Way Weather, his lovely manse of many rooms and sculpted towers in the hills above the north edge of Were Woods, and, using a less stressful variation on the ancient Spell of Forlorn Encystment, sank his manse, his beautiful gardens, and twelve of his thirteen servants some forty-five miles beneath the surface of the Dying Earth. Shrue’s diabolic equipment, mementos, the bulk of his library, and the curios and ancillary demons he’d collected over the many centuries would be safe there underground, unless—of course—the great red sun actually swallowed the Dying Earth this time around. As for the truly amazing collection of flowers, trees, and exo

titerra plants and animals from his garden (not to mention his twelve stored human and near-human servants), they were wrapped in miniature Omnipotent Eggs, each egg wrapped in turn in its own Field of Temporal Stasis, so Shrue was confident that if the Earth and he survived, so would his domestic staff, awakening months or years or centuries or millennia hence as if rising from a restorative sleep.

Shrue kept only Old Blind Bommp, his man-servant and irreplaceable chef, to travel north with him to his remote summer cottage on the shores of the Lesser Polar Sea. Bommp knew his way around the polar cottage and its protected grounds there as well as he’d memorized the many rooms, turrets, tunnels, secret passages, stairways, guest houses, kitchens, gardens, and grounds of Way Weather itself.

As for the scores of minor devils, demons, sandestins, stone-ghouls, elementals, archvaults, daihaks, and (a few) rune-ghosts that Shrue kept at his beck and call, all of these save one sank below with Way Weather manse in the Modified Spell of Forlorn Encystment—yet each remained capable of being summoned in an instant by the briefest incantation.

The only otherish entity that Shrue the diabolist took with him to the cottage on the shores of the Lesser Polar Sea was KirdriK.

KirdriK was an odd hybrid of forces—part mutant sandestin from the 14th Aeon, part full-formed daihak in the order of Undra-Hadra. Only the greatest arch-magicians in the history of the post-Yellow Sun Dying Earth dared to attempt to control a mature daihak-sandestin hybrid. Shrue the diabolist kept three such terrifying creatures in his employ at once. Two now rested forty-five miles beneath the surface of the earth, but KirdriK jinkered north along with Shrue and Old Blind Bommp, cushioned atop one of the larger rugs from Way Weather’s grand hall. The jinkered carpet traveled at night, never rising above five thousand feet, and was protected by Shrue’s Omnipotent Sphere as well as by the ancient carpet’s own Cloud of Concealment, generated by the warp and woof of its softly singing incantatorial threads.

It had taken Shrue thirty-five years to summon KirdriK, another sixty-nine years to fully bind him, ten years to teach the monster a language other than its native curses and snarls, and more than twice a hundred years to make the halfbreed daihak superficially civil enough to take his place among Shrue’s staff of loyal domestics. Shrue thought that it was time the creature began earning his keep.

· · ·

Shrue’s first few weeks at his polar cottage were as quiet and uneventful as even the most retiring diabolist might have wished.

Early each morning, Shrue would rise, exercise his personal combat skills for an hour with a private avatar bound during the days of Ranfitz’s War, and then retire to his garden for a long session of meditation. None of Shrue’s former colleagues or competitors had known it, but the diabolist had long been adept in the Slow Discipline of Derh Shuhr, and Shrue exercised those demanding mental abilities every day.

The garden itself, while modest in comparison with that of Way Weather and also mostly sunken below the level of the surrounding lawns and low tundra growth, was still impressive. Shrue’s tastes ran contrary to most magi’s love of the wildly exotic—feathered parasol trees, silver and blue tantalum foil leaves, air-anemone trifoliata, transparent trunks and the like—and tended, as Shrue himself did, toward the more restrained and visually pleasing: tri-aspen imported from such old worlds as Yperio and Grauge, night-blooming rockwort and windchime sage, and self-topiarying Kingreen.

In late morning, when the huge red sun had finally freed itself from the southern horizon, Shrue would walk down the long dock, unfold the masts and sails of his sleek quintfoil catamaran, and sail the limpid seas of the Lesser Polar Sea, exploring coves and bays as he went. There were seamonsters even beneath the surface of the tideless, shallow polar seas, of course—codorfins and forty-foot water shadows the most common—but even such aquatic predators had long-since learned not to attempt to molest an arch-mage of Shrue the diabolist’s reputation.

Then, after an hour or two of calm sailing, he would return and enjoy the abstemious lunch of pears, fresh-baked pita, Bernish pasta, and cold gold wine that Bommp had prepared for him.

In the afternoon, Shrue would work in one of his workshops (usually the Green Cabal) for several hours, and then emerge for a late afternoon cordial in the library and to hear KirdriK’s daily patrol report and finally to open his mail.

This day, KirdriK shuffled into the library bowlegged and naked except for an orange breachclout that did nothing to hide either the monster’s gender or his odd build. The smallest the daihak could contract his physical shape still left him almost twice as tall as any average human. With his blue scales, yellow eyes, six fingers, gill slits along neck and abdomen, multiple rows of incisors, and purple feathers flowing from his chest and erupting along the red crestbones of his skull—not to mention the five-foot long dorsal flanges that vented wide and razor-sharp whenever KirdriK became agitated or simply wanted to impress his foes—Shrue had to dress his servant in the loose, flowing blue robes and veil-mesh of a Firschnian monk whenever he took him out in public.

Today, as mentioned, the daihak wore only the obscene orange breachclout. After he’d shuffled before the diabolist and knuckled his forehead in a parody of a salute—or perhaps just to preen the white feather-floss that grew from his barnacle-sharp brow—KirdriK went through his inevitable rumbling, growling, and spitting sounds before being able to speak. (Shrue had long since spell-banished and pain-conditioned the cursing and roaring out of the daihak—at least in the magician’s presence—but KirdriK still tried.)

“What have you seen today?” asked Shrue.

(rumble, spit) “A grizzpol, a man’s hour’s walk east along the shore,” rumbled KirdriK in tones that approached the subsonic, but which Shrue had modified his ears to pick up.

“Hmmm,” murmured the diabolist. Grizzpols were rare. The huge tan bears, recreated by a polar-dwelling magician named Hrestrk-Grk in the 19th Aeon, were reported, by legend at least, to have originated from the crossbreeding of fabled white bears that had lived here millions of years earlier when the poles were cold and huge, with vicious brown bears from the steppes further south. “What did you do with the grizzpol?” asked Shrue.

“Ate it for lunch.”

“Anything else?” asked the diabolist.

“I came across five Deodands lurking about five miles into the Final Forest,” rumbled KirdriK.

Shrue’s always-arched eyebrow raised a scintilla higher. Deodands were not native to the polar forests or gorse steppes. “Oh,” he said mildly. “Why do you think they were this far north?”

“Trying to claim the magus-bounty,” growled KirdriK and showed all three or four hundred of his serriated and serrated teeth.

Shrue smiled. “And what did you do with these five, KirdriK?”

Still showing his teeth, the daihak lifted a fist over Shrue’s tea table, opened his hand, and let sixty or so Deodane fangs rattle onto the parqueted wood.

Shrue sighed. “Collect those,” he ordered. “Have Bommp grind them into the usual powder and store them in the usual apothecam jars in the Blue Diadem workshop.”

KirdriK growled and shifted from one huge, taloned foot to the other, his hands twitching and jerking like a strangler’s. Shrue knew that the daihak tested his restraint bonds and spells every hour of every day.

“That’s all,” said the diabolist. “You are dismissed.”

KirdriK departed by the tallest of the five doorways that opened into the library, and Shrue opened the window that looked into his courtyard eyrie and called in the day’s batch of newly arrived sparlings.

There were nine of the small, gray, songless birds this day and they lined up on the arm of Shrue’s chair. As each approached the magus’s hand, Shrue made a pass, opened the bird’s tiny chest, and drew out its second heart, dropping each in turn into an empty teacup with a soft splat. Shrue then conjured a new and preprogrammed blank recording heart for each sparling and set it in place. When he was finished, the nine birds f

lew out the window, rose out of the courtyard, and went about their business to the south.

Shrue rang for Old Bommp and when the tiny man padded silently into the room, said, “There are only nine today. Please add some green tea to bring the flavor up.” Bommp nodded, unerringly found the teacup that sat in its usual place, and padded away with the same blind but barefoot stealth by which he’d entered. Five minutes later, he was back with Shrue’s steaming tea. When the servant was gone, the diabolist sipped and then closed his eyes to read and see his mail.

It seemed that Ildefonse the Preceptor had returned from wherever he had fled off the Dying Earth because he had forgotten some of his velvet formal suits. While decloaking his pretentious manse, the pompous magician had been set upon by a mob of more than two thousand local peasants and pelgranes and Deodands working in unison—very strange—and they had Ildefonse’s mouth taped, eyes covered, and fingers immobilized before the foolish old magician could waggle a finger or mutter a curse, much less cast a spell. They stripped the old fool of his clothes, amulets, talismen, and charms. As soon as they touched his body with their bare hands, Ildefonse’s defensive Egg shimmered into place, but the mob simply carried that into town and buried it in a mound of dung piled to the ceiling of the one-room stone gaol in the center of the Commons, placing twenty-four guards and five hungry Deodands around the gaol and dungheap.

Shrue chuckled and went on to the rest of the sparling-heart news.

Ulfänt Banderōz was dead.

Shrue sat bolt upright in his chair, sending the teacup flying and shattering.

Ulfänt Banderōz was dead.

Shrue the diabolist leaped to his feet, clasped his hands behind his back, and began rapidly pacing the confines of his great library, eyes still closed, as blind as old Bommp, but, like Bommp, so familiar with the perimeter and carpet and hardwood and shelves and tables and other furniture in his great library that he never jostled a curio or open volume. Shrue, whose nature it was never to cease concentrating, was concentrating more fiercely and single-mindedly than he had in some time.

The Terror

The Terror Endymion

Endymion Hyperion

Hyperion The Crook Factory

The Crook Factory Ilium

Ilium Phases of Gravity

Phases of Gravity Hardcase

Hardcase Fires of Eden

Fires of Eden Children of the Night

Children of the Night Muse of Fire

Muse of Fire Drood

Drood The Fifth Heart

The Fifth Heart Carrion Comfort

Carrion Comfort The Hollow Man

The Hollow Man Summer of Night

Summer of Night The Fall of Hyperion

The Fall of Hyperion Black Hills

Black Hills A Winter Haunting

A Winter Haunting Hard Freeze

Hard Freeze Prayers to Broken Stones

Prayers to Broken Stones Hard as Nails

Hard as Nails The Guiding Nose of Ulfant Banderoz

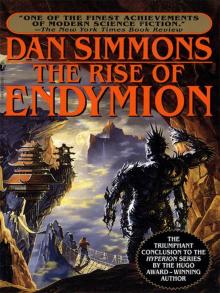

The Guiding Nose of Ulfant Banderoz The Rise of Endymion

The Rise of Endymion Orphans of the Helix

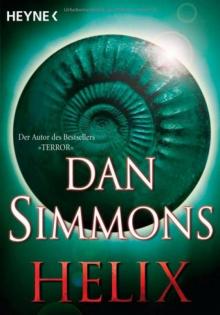

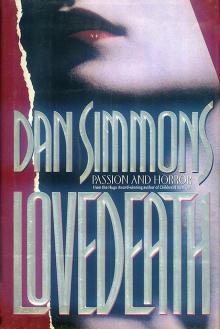

Orphans of the Helix Lovedeath

Lovedeath Olympos

Olympos Darwin's Blade

Darwin's Blade Song of Kali

Song of Kali Worlds Enough & Time: Five Tales of Speculative Fiction

Worlds Enough & Time: Five Tales of Speculative Fiction The Abominable

The Abominable The Death of the Centaur

The Death of the Centaur Hard as Nails jk-3

Hard as Nails jk-3 Worlds Enough & Time

Worlds Enough & Time Joe Kurtz Omnibus

Joe Kurtz Omnibus The Hyperion Cantos 4-Book Bundle

The Hyperion Cantos 4-Book Bundle Rise of Endymion

Rise of Endymion Hard Freeze jk-2

Hard Freeze jk-2 Olympos t-2

Olympos t-2 The Abominable: A Novel

The Abominable: A Novel Hyperion h-1

Hyperion h-1 Remembering Siri

Remembering Siri Black Hills: A Novel

Black Hills: A Novel Ilium t-1

Ilium t-1 Hardcase jk-1

Hardcase jk-1 Hyperion 01 - Hyperion

Hyperion 01 - Hyperion