- Home

- Dan Simmons

The Hyperion Cantos 4-Book Bundle Page 13

The Hyperion Cantos 4-Book Bundle Read online

Page 13

The Consul looked at the rubble of the Shrike Temple.

“This pilgrimage was over before you got here,” said Governor-General Theo Lane. “Will you come back to the consulate with me … at least in an advisory capacity?”

“I’m sorry,” said the Consul. “I can’t.”

Theo turned without a word, dropped into the skimmer, and lifted off. His military escort followed as a blur in the rain.

It was raining harder now. The group moved closer together in the growing darkness. Weintraub had rigged a makeshift hood over Rachel and the noise of the rain on plastic made the baby cry.

“What now?” said the Consul, looking around at the night and narrow streets. Their luggage lay heaped in a soggy pile. The world smelled of ashes.

Martin Silenus grinned. “I know a bar.”

It turned out that the Consul also knew the bar; he had all but lived in Cicero’s for most of his eleven-year assignment on Hyperion.

Unlike most things in Keats, on Hyperion, Cicero’s was not named after some piece of pre-Hegira literary trivia. Rumor had it that the bar was named after a section of an Old Earth city—some said Chicago, USA, others were sure it was Calcutta, AIS—but only Stan Leweski, owner and great-grandson of the founder, knew for sure, and Stan had never revealed its secret. The bar itself had overflowed over the century and a half of its existence from a walk-up loft in one of Jacktown’s sagging older buildings along the Hoolie River to nine levels in four sagging old buildings along the Hoolie. The only consistent elements of decor at Cicero’s over the decades were the low ceilings, thick smoke, and constant background babble which offered a sense of privacy in the midst of bustle.

There was no privacy this night. The Consul and the others paused as they carried their gear through the Marsh Lane entrance.

“Jesus wept,” muttered Martin Silenus.

Cicero’s looked as if it had been invaded by barbarian hordes. Every chair was filled, every table occupied, mostly by men, and the floors were littered with packs, weapons, bedrolls, antiquated comm equipment, ration boxes, and all of the other detritus of an army of refugees … or perhaps a refugee army. The heavy air of Cicero’s, which once had been filled with the blended scent of broiling steaks, wine, stim, ale, and T-free tobacco, was now laden with the overlapping smells of unwashed bodies, urine, and hopelessness.

At that moment the huge form of Stan Leweski materialized out of the gloom. The bar owner’s forearms were as huge and heavy as ever, but his forehead had advanced more than a few centimeters against the receding tangle of black hair and there were more creases than the Consul remembered around the dark eyes. Those eyes were wide now as Leweski stared at the Consul. “Ghost,” he said.

“No.”

“You are not dead?”

“No.”

“By damn!” declared Stan Leweski and, grasping the Consul by the upper arms, picked him up as easily as a man would lift a five-year-old. “By damn! You are not dead. What are you doing here?”

“Checking your liquor license,” said the Consul. “Put me down.”

Leweski carefully set the Consul down, tapped his shoulders, and grinned. He looked at Martin Silenus and the grin changed to a frown. “You look familiar but I have never seen you before.”

“I knew your great-grandfather,” said Silenus. “Which reminds me, do you have any of that pre-Hegira ale left? The warm, British stuff that tastes like recycled moose piss. I could never get enough of that.”

“Nothing left,” said Leweski. He pointed at the poet. “By damn. Grandfather Jiri’s trunk. That old holo of the satyr in the original Jacktown. Can it be?” He stared at Silenus and then at the Consul, touching them both gingerly with a massive forefinger. “Two ghosts.”

“Six tired people,” said the Consul. The baby began crying again. “Seven. Do you have space for us?”

Leweski turned in a half circle, hands spread, palms up. “It is all like this. No space left. No food. No wine.” He squinted at Martin Silenus. “No ale. Now we have become a big hotel with no beds. The SDF bastards stay here without paying and drink their own upcountry rotgut and wait for the world to end. That will happen soon enough, I think.”

The group was standing in what had once been the entrance mezzanine. Their heaped luggage joined a riot of gear already littering the floor. Small clusters of men shouldered their way through the throng and cast appraising glances at the newcomers—especially at Brawne Lamia. She returned their stares with a flat, cold glare.

Stan Leweski looked at the Consul for a moment. “I have a balcony table. Five of those SDF Death Commandos have been parked there for a week, telling everyone and each other how they are going to wipe out the Ouster Legions with their bare hands. You want the table, I will throw the teat-suckers out.”

“Yes,” said the Consul.

Leweski had turned to leave when Lamia stopped him with a hand on his arm. “Would you like a little help?” she asked.

Stan Leweski shrugged, grinned. “I do not need it, but I might like it. Come.”

They disappeared into the crowd.

The third-floor balcony had just enough room for the splintered table and six chairs. Despite the insane crowding on the main floors, stairs, and landings, no one had challenged them for the space after Leweski and Lamia threw the protesting Death Commandos over the railing and into the river nine meters below. Somehow Leweski had managed to send up a tankard of beer and a basket of bread and cold beef.

The group ate in silence, obviously suffering more than the usual amount of postfugue hunger, fatigue, and depression. The darkness of the balcony was relieved only by dim, reflected light from deeper within Cicero’s and by the lanterns on passing river barges. Most of the buildings along the Hoolie were dark but other city lights reflected from low clouds. The Consul could make out the ruins of the Shrike Temple half a kilometer upriver.

“Well,” said Father Hoyt, obviously recovered from the heavy dose of ultramorph and teetering on the delicate balance between pain and sedation, “what do we do next?”

When no one answered, the Consul closed his eyes. He refused to take the lead in anything. Sitting on the balcony at Cicero’s, it was all too easy to fall back into the rhythms of a former life; he would drink until the early morning hours, watch the predawn meteor showers as the clouds cleared, and then stagger to his empty apartment near the market, going into the consulate four hours later showered, shaved, and seemingly human except for the blood in his eyes and the insane ache in his skull. Trusting in Theo—quiet, efficient Theo—to get him through the morning. Trusting in luck to get him through the day. Trusting in the drinking at Cicero’s to get him through the night. Trusting in the unimportance of his posting to get him through life.

“You are all ready to leave for the pilgrimage?”

The Consul’s eyes snapped open. A hooded figure stood in the doorway and for a second the Consul thought it was Het Masteen, but then he realized that this man was much shorter, his voice not accented with the stilted Templar consonants.

“If you are ready, we must go,” said the dark figure.

“Who are you?” asked Brawne Lamia.

“Come quickly,” was the shadow’s only reply.

Fedmahn Kassad stood, bending to keep his head from striking the ceiling, and detained the robed figure, flipping back the man’s hood with a flick of his left hand.

“An android!” said Lenar Hoyt, staring at the man’s blue skin and blue-on-blue eyes.

The Consul was less surprised. For more than a century it had been illegal to own androids in the Hegemony, and none had been biofactured for almost that long, but they were still used for manual labor in remote parts of backwater, noncolony worlds—worlds like Hyperion. The Shrike Temple had used androids extensively, complying with the Church of the Shrike doctrine which proclaimed that androids were free from original sin, therefore spiritually superior to humankind and—incidentally—exempt from the Shrike’s terrible and inevitable

retribution.

“You must come quickly,” whispered the android, setting his hood in place.

“Are you from the Temple?” asked Lamia.

“Quiet!” snapped the android. He glanced into the hall, turned back, and nodded. “We must hurry. Please follow me.”

All of them stood and then hesitated. The Consul watched as Kassad casually unsealed the long leather jacket he was wearing. He caught the briefest glimpse of a deathwand tucked in the Colonel’s belt. Normally the Consul would have been appalled by even the thought of a deathwand nearby—the slightest mistaken touch could purée every synapse on the balcony—but at this moment he was oddly reassured by the sight of it.

“Our luggage …” began Weintraub.

“It has been seen to,” whispered the hooded man. “Quickly now.”

The group followed the android down the stairs and into the night, their movement as tired and passive as a sigh.

The Consul slept late. Half an hour after sunrise a rectangle of light found its way between the porthole’s shutters and fell across his pillow. The Consul rolled away and did not wake. An hour after that there came a loud clatter as the tired mantas which had pulled the barge all night were released and fresh ones harnessed. The Consul slept on. In the next hour the footsteps and cries of the crew on the deck outside his stateroom grew louder and more persistent, but it was the warning claxon below the locks at Karla which finally brought him up out of his sleep.

Moving slowly in the druglike languor of fugue hangover, the Consul bathed as best he could with only basin and pump, dressed in loose cotton trousers, an old canvas shirt, and foam-soled walking shoes, and found his way to the mid-deck.

Breakfast had been set out on a long sideboard near a weathered table which could be retracted into the deck planking. An awning shaded the eating area and the crimson and gold canvas snapped to the breeze of their passage. It was a beautiful day, cloudless and bright, with Hyperion’s sun making up in ferocity what it lacked in size.

M. Weintraub, Lamia, Kassad, and Silenus had been up for some time. Lenar Hoyt and Het Masteen joined the group a few minutes after the Consul arrived.

The Consul helped himself to toasted fish, fruit, and orange juice at the buffet and then moved to the railing. The water was wide here, at least a kilometer from shore to shore, and its green and lapis sheen echoed the sky. At first glance the Consul did not recognize the land on either side of the river. To the east, periscope-bean paddies stretched away into the haze of distance where the rising sun reflected on a thousand flooded surfaces. A few indigenie huts were visible at the junction of paddy dikes, their angled walls made of bleached weirwood or golden halfoak. To the west, the bottomland along the river was overgrown with low tangles of gissen, womangrove root, and a flamboyant red fern the Consul did not recognize, all growing around mud marshes and miniature lagoons which stretched another kilometer or so to bluffs where scrub everblues clung to any bare spot between granite slabs.

For a second the Consul felt lost, disoriented on a world he thought he knew well, but then he remembered the claxon at the Karla Locks and realized that they had entered a rarely used stretch of the Hoolie north of Doukhobor’s Copse. The Consul had never seen this part of the river, having always traveled on or flown above the Royal Transport Canal which lay to the west of the bluffs. He could only surmise that some danger or disturbance along the main route to the Sea of Grass had sent them this back way along bypassed stretches of the Hoolie. He guessed that they were about a hundred and eighty kilometers northwest of Keats.

“It looks different in the daylight, doesn’t it?” said Father Hoyt.

The Consul looked at the shore again, not sure what Hoyt was talking about; then he realized the priest meant the barge.

It had been strange—following the android messenger in the rain, boarding the old barge, making their way through its maze of tessellated rooms and passages, picking up Het Masteen at the ruins of the Temple, and then watching the lights of Keats fall astern.

The Consul remembered those hours before and after midnight as from a fatigue-blurred dream, and he imagined the others must have been just as exhausted and disoriented. He vaguely remembered his surprise that the barge’s crew were all android, but mostly he recalled his relief at finally closing the door of his stateroom and crawling into bed.

“I was talking to A. Bettik this morning,” said Weintraub, referring to the android who had been their guide. “This old scow has quite a history.”

Martin Silenus moved to the sideboard to pour himself more tomato juice, added a dash of something from the flask he carried, and said, “It’s obviously been around a bit. The goddamn railings’ve been oiled by hands, the stairs worn by feet, the ceilings darkened by lamp soot, and the beds beaten saggy by generations of humping. I’d say it’s several centuries old. The carvings and rococo finishes are fucking marvelous. Did you notice that under all the other scents the inlaid wood still smells of sandalwood? I wouldn’t be surprised if this thing came from Old Earth.”

“It does,” said Sol Weintraub. The baby, Rachel, slept on his arm, softly blowing bubbles of saliva in her sleep. “We’re on the proud ship Benares, built in and named after the Old Earth city of the same name.”

“I don’t remember hearing of any Old Earth city with that name,” said the Consul.

Brawne Lamia looked up from the last of her breakfast. “Benares, also known as Varanasi or Gandhipur, Hindu Free State. Part of the Second Asian Co-prosperity Sphere after the Third Sino-Japanese War. Destroyed in the Indo-Soviet Muslim Republic Limited Exchange.”

“Yes,” said Weintraub, “the Benares was built quite some time before the Big Mistake. Mid-twenty-second century, I would guess. A. Bettik informs me that it was originally a levitation barge …”

“Are the EM generators still down there?” interrupted Colonel Kassad.

“I believe so,” said Weintraub. “Next to the main salon on the lowest deck. The floor of the salon is clear lunar crystal. Quite nice if we were cruising at two thousand meters … quite useless now.”

“Benares,” mused Martin Silenus. He ran his hand lovingly across a time-darkened railing. “I was robbed there once.”

Brawne Lamia put down her coffee mug. “Old man, are you trying to tell us that you’re ancient enough to remember Old Earth? We’re not fools, you know.”

“My dear child,” beamed Martin Silenus, “I am not trying to tell you anything. I just thought it might be entertaining—as well as edifying and enlightening—if at some point we exchanged lists of all the locations at which we have either robbed or been robbed. Since you have the unfair advantage of having been the daughter of a senator, I am sure that your list would be much more distinguished … and much longer.”

Lamia opened her mouth to retort, frowned, and said nothing.

“I wonder how this ship got to Hyperion?” murmured Father Hoyt. “Why bring a levitation barge to a world where EM equipment doesn’t work?”

“It would work,” said Colonel Kassad. “Hyperion has some magnetic field. It just would not be reliable in holding anything airborne.”

Father Hoyt raised an eyebrow, obviously at a loss to see the distinction.

“Hey,” cried the poet from his place at the railing, “the gang’s all here!”

“So?” said Brawne Lamia. Her lips all but disappeared into a thin line whenever she spoke to Silenus.

“So we’re all here,” he said. “Let’s get on with the storytelling.”

Het Masteen said, “I thought it had been agreed that we would tell our respective stories after the dinner hour.”

Martin Silenus shrugged. “Breakfast, dinner, who the fuck cares? We’re assembled. It’s not going to take six or seven days to get to the Time Tombs, is it?”

The Consul considered. Less than two days to get as far as the river could take them. Two more days, or less if the winds were right, on the Sea of Grass. Certainly no more than one more day to cross the moun

tains. “No,” he said. “Not quite six days.”

“All right,” said Silenus, “then let’s get on with the telling of tales. Besides, there’s no guarantee that the Shrike won’t come calling before we knock on his door. If these bedtime stories are supposed to be helpful to our survival chances in some way, then I say let’s hear from everyone before the contributors start getting chopped and diced by that ambulatory food processor we’re so eager to visit.”

“You’re disgusting,” said Brawne Lamia.

“Ah, darling,” smiled Silenus, “those are the same words you whispered last night after your second orgasm.”

Lamia looked away. Father Hoyt cleared his throat and said, “Whose turn is it? To tell a story, I mean?” The silence stretched.

“Mine,” said Fedmahn Kassad. The tall man reached into the pocket of his white tunic and held up a slip of paper with a large 2 scribbled on it.

“Do you mind doing this now?” asked Sol Weintraub.

Kassad showed a hint of a smile. “I wasn’t in favor of doing it at all,” he said, “but if it were done when ‘tis done, then’ twere well it were done quickly.”

“Hey!” cried Martin Silenus. “The man knows his pre-Hegira playwrights.”

“Shakespeare?” said Father Hoyt.

“No,” said Silenus. “Lerner and fucking Lowe. Neil buggering Simon. Hamel fucking Posten.”

“Colonel,” Sol Weintraub said formally, “the weather is nice, none of us seems to have anything pressing to do in the next hour or so, and we would be obliged if you would share the tale of what brings you to Hyperion on the Shrike’s last pilgrimage.”

Kassad nodded. The day grew warmer as the canvas awning snapped, the decks creaked, and the levitation barge Benares worked its steady way upstream toward the mountains, the moors, and the Shrike.

THE SOLDIER’S TALE:

THE WAR LOVERS

It was during the Battle of Agincourt that Fedmahn Kassad encountered the woman he would spend the rest of his life seeking.

The Terror

The Terror Endymion

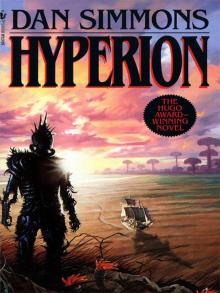

Endymion Hyperion

Hyperion The Crook Factory

The Crook Factory Ilium

Ilium Phases of Gravity

Phases of Gravity Hardcase

Hardcase Fires of Eden

Fires of Eden Children of the Night

Children of the Night Muse of Fire

Muse of Fire Drood

Drood The Fifth Heart

The Fifth Heart Carrion Comfort

Carrion Comfort The Hollow Man

The Hollow Man Summer of Night

Summer of Night The Fall of Hyperion

The Fall of Hyperion Black Hills

Black Hills A Winter Haunting

A Winter Haunting Hard Freeze

Hard Freeze Prayers to Broken Stones

Prayers to Broken Stones Hard as Nails

Hard as Nails The Guiding Nose of Ulfant Banderoz

The Guiding Nose of Ulfant Banderoz The Rise of Endymion

The Rise of Endymion Orphans of the Helix

Orphans of the Helix Lovedeath

Lovedeath Olympos

Olympos Darwin's Blade

Darwin's Blade Song of Kali

Song of Kali Worlds Enough & Time: Five Tales of Speculative Fiction

Worlds Enough & Time: Five Tales of Speculative Fiction The Abominable

The Abominable The Death of the Centaur

The Death of the Centaur Hard as Nails jk-3

Hard as Nails jk-3 Worlds Enough & Time

Worlds Enough & Time Joe Kurtz Omnibus

Joe Kurtz Omnibus The Hyperion Cantos 4-Book Bundle

The Hyperion Cantos 4-Book Bundle Rise of Endymion

Rise of Endymion Hard Freeze jk-2

Hard Freeze jk-2 Olympos t-2

Olympos t-2 The Abominable: A Novel

The Abominable: A Novel Hyperion h-1

Hyperion h-1 Remembering Siri

Remembering Siri Black Hills: A Novel

Black Hills: A Novel Ilium t-1

Ilium t-1 Hardcase jk-1

Hardcase jk-1 Hyperion 01 - Hyperion

Hyperion 01 - Hyperion